Aboriginal Art

Contemporary Aboriginal dancers

Contemporary Aboriginal dancers

|

|

I am not an expert on Aboriginal art, but I taught for 15

years at the Australian National University, during which I

taught Australian art and my husband worked at the

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Studies. So we were very involved with

Aboriginal issues and Aboriginal art during an eventful

time.

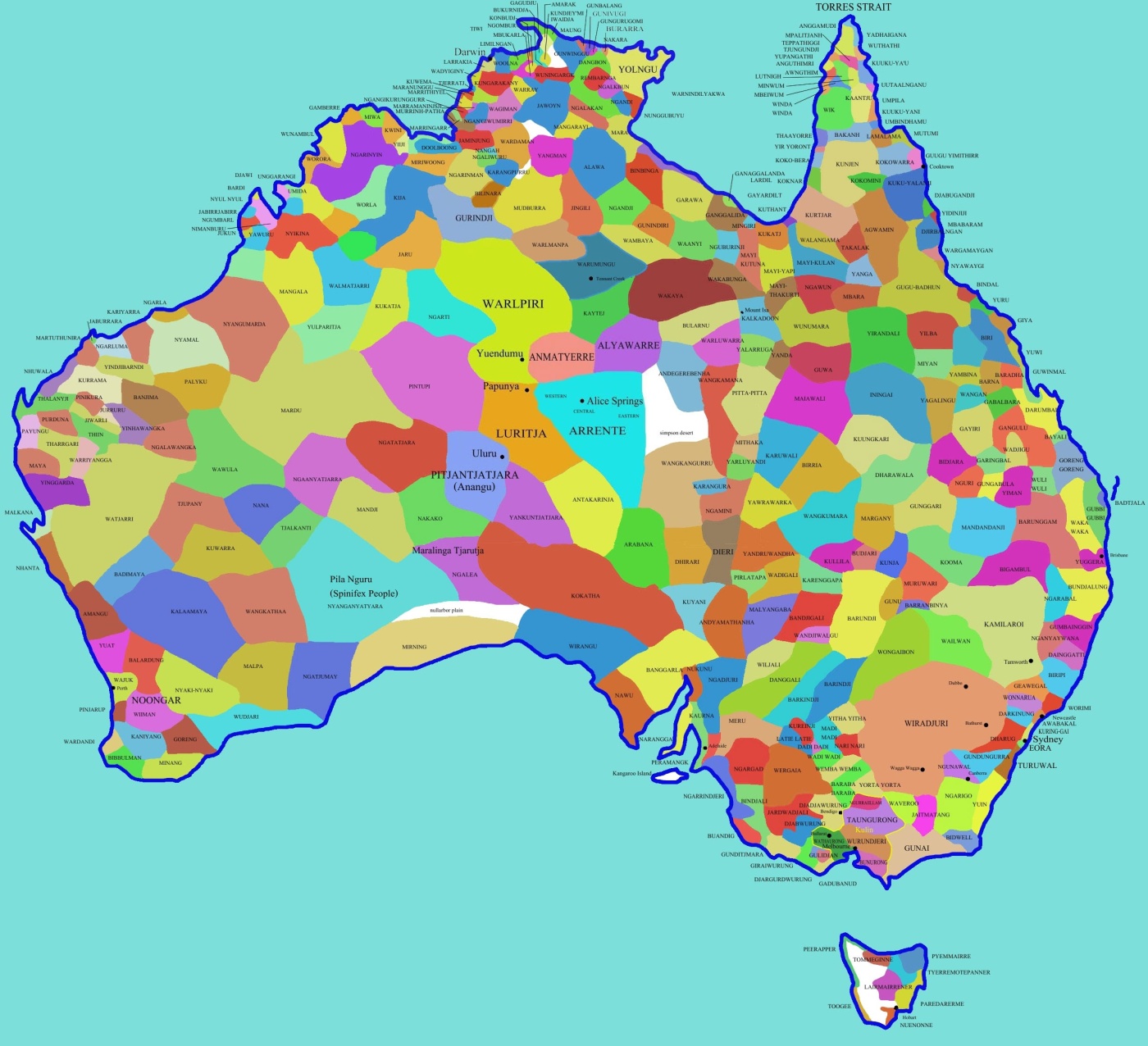

Aboriginal languages:

"In the late 18th century, there were

more than 250 distinct Aboriginal social

groupings and a similar number of languages or

varieties. At the start of the 21st century, fewer than

150 Aboriginal languages remain in daily use, and

all except only 13, which are still being transmitted to

children, are highly endangered."

--no permanent settlements, very little material

culture--what used to be called “hard primitivism” as

opposed to the “soft” primitivism of Polynesians, for

example

--some 200 distinct languages, as many as a thousand

dialects of these

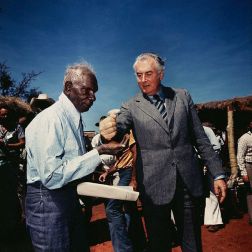

Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pours soil into the hands of

traditional land owner Vincent Lingiari, 16 August

1975, Northern Territory. This is the historical

moment that is the theme of Paul Kelly's great song, "From

Little Things Big Things Grow". Lignari led the strike by

Aboriginal stockmen to reclaim their traditional land,

beginning the process of overturning the concept of "terra

nullius".

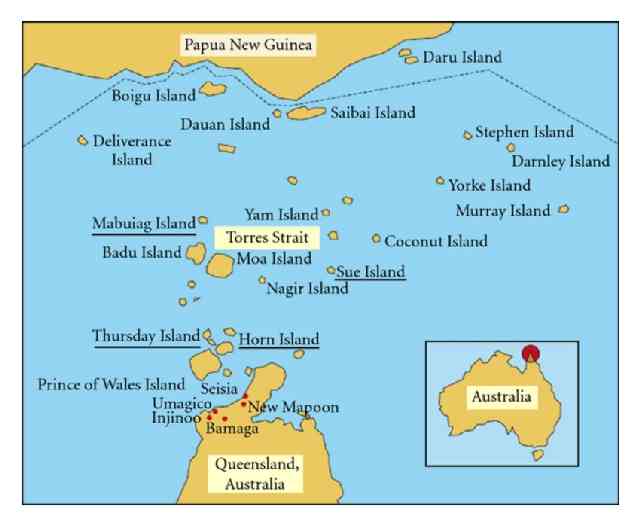

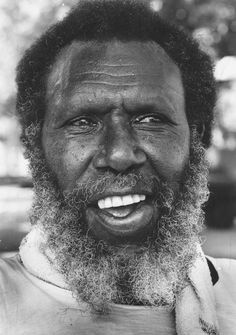

EX: Eddie Mabo with the Torres Strait Islander flag

and in later life:

Eddie Mabo (c. 29 June 1936 – 21 January 1992[1])

was an Indigenous Australian

man from the Torres Strait Islands

known for his role in campaigning for Indigenous land rights

and for his role in a landmark decision of the High Court of Australia

which overturned the legal doctrine of terra nullius ("nobody's

land") which characterised Australian law with regard to

land and title.[From Wikipedia]

One of the continuing vexed issues: is the production

of "artworks" by Aboriginal people properly placed in the

realm of ethnography or can it be seen as fine art in the

Western art tradition?

--art market’s implications for tribal, indigenous people --what are we to make of our AESTHETIC response, as non-indigenous people, to images that for the maker have very different meanings?

Aborigines have been in Australia for 40-60,000 years, and

are considered by many to be the oldest enduring and

continuous culture. Aboriginal Australians are descendents

of the first people to leave Africa up to 75,000 years ago,

a genetic study has found, confirming they may have the

oldest continuous culture on the planet. IMPORTANT:

Aboriginal culture is NOT one culture, but consists of small

nomadic groups, each with own language--in some places with

populations as little as 1,000, three different languages

will co-exist.

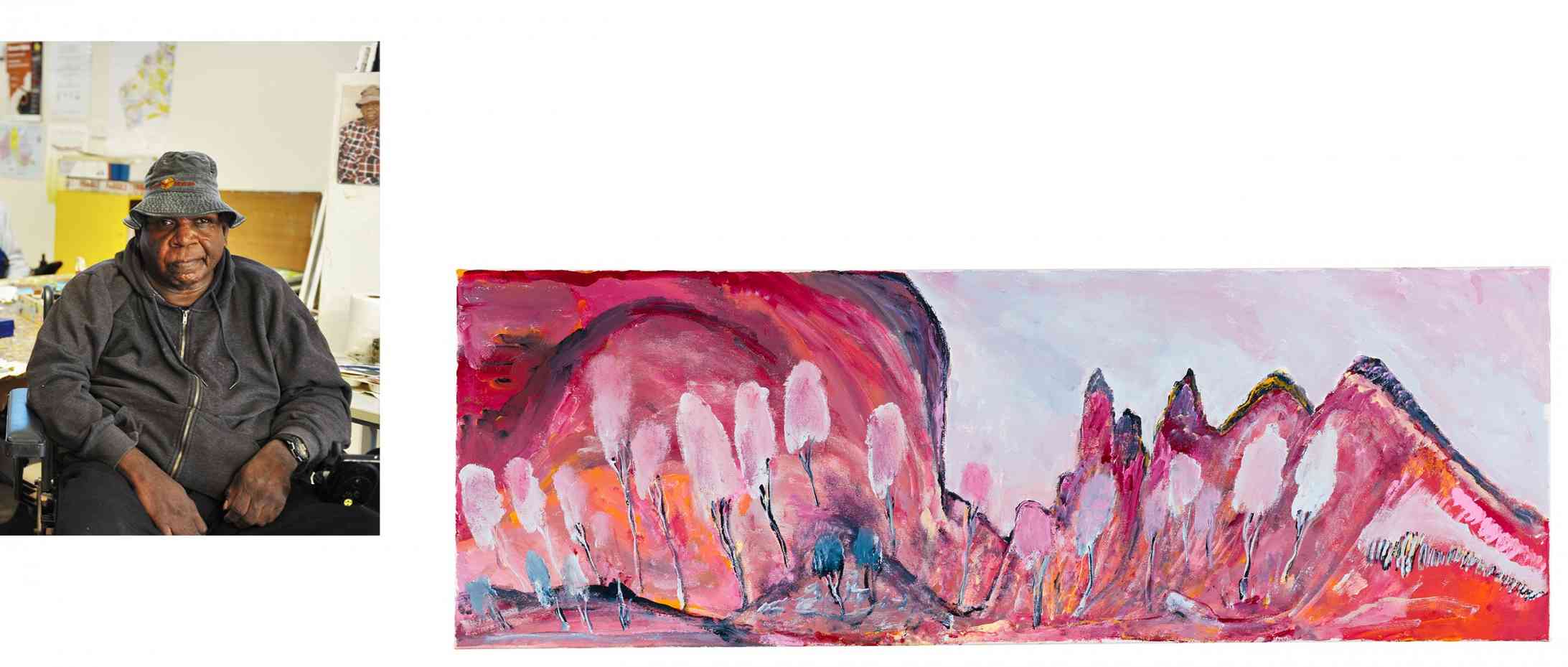

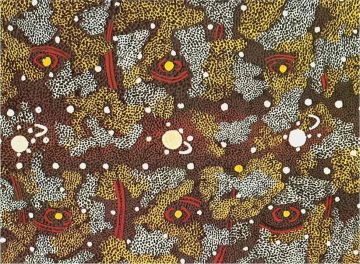

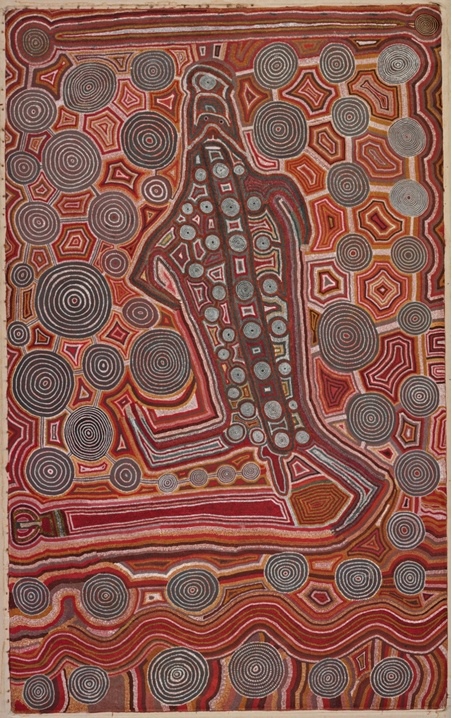

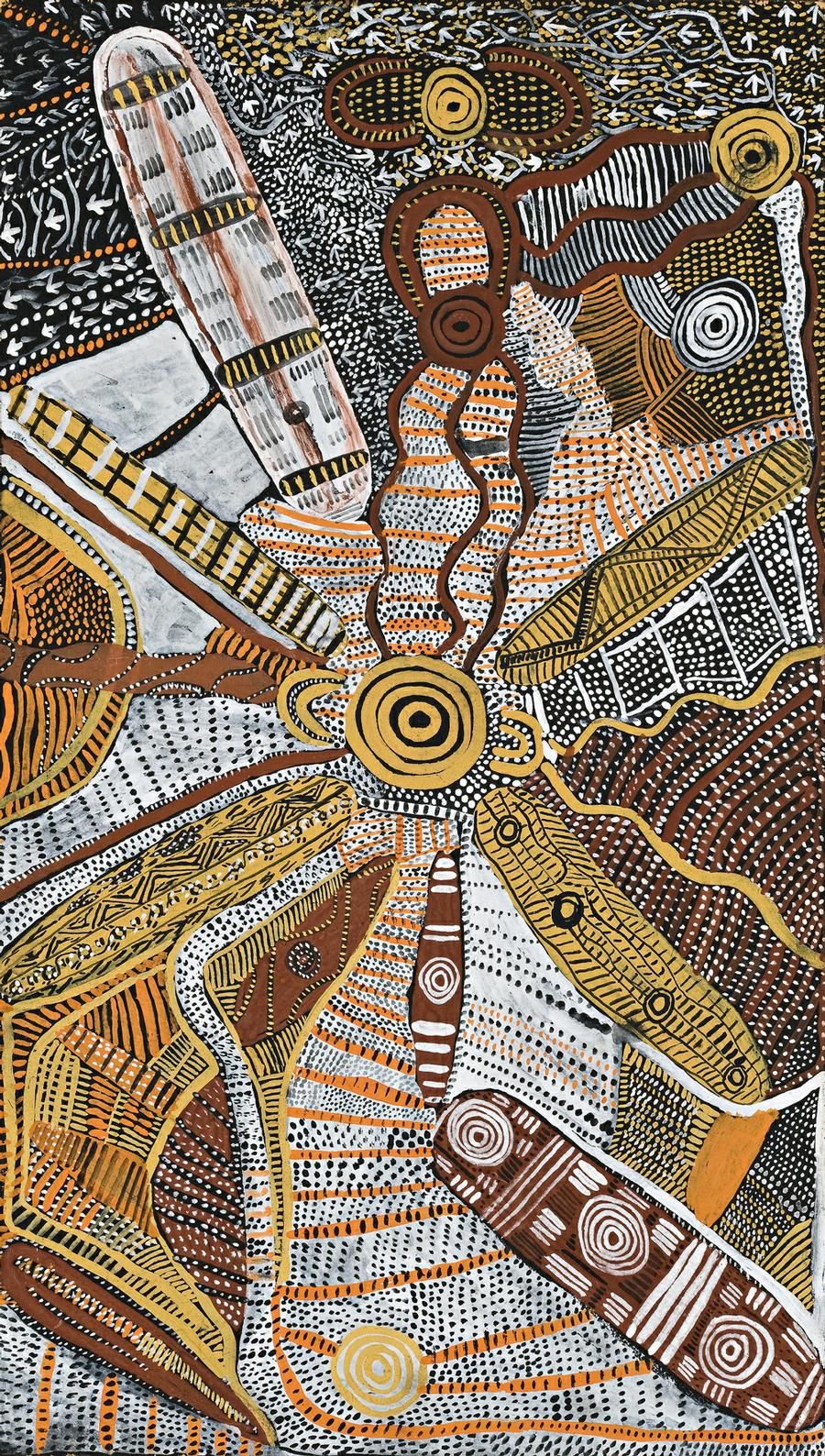

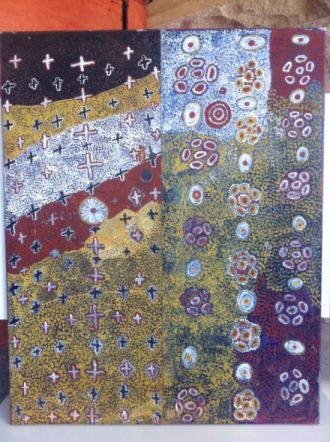

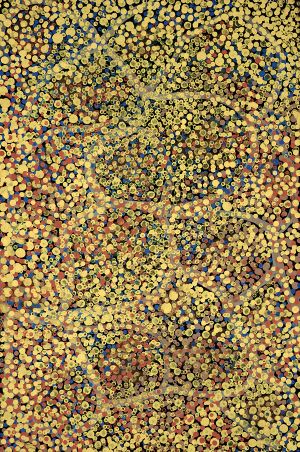

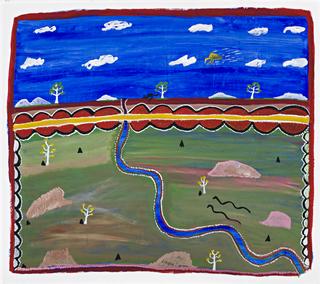

Adrian Jangala Robertson, Yalpirakinu, 2020 (Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Award winner).

He at Yuendumu, his paintings consistently refer to the desert mountain, ridges and tress which are part of Yalpirakinu, his home land.

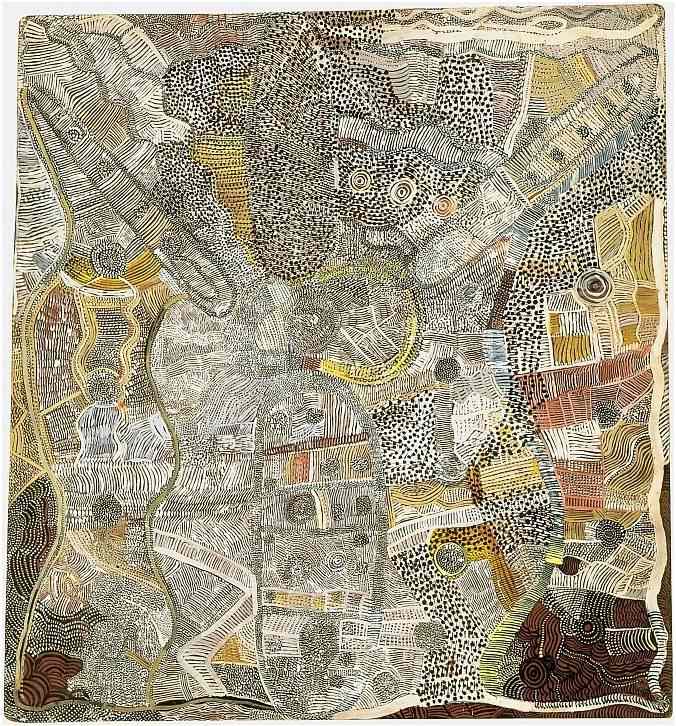

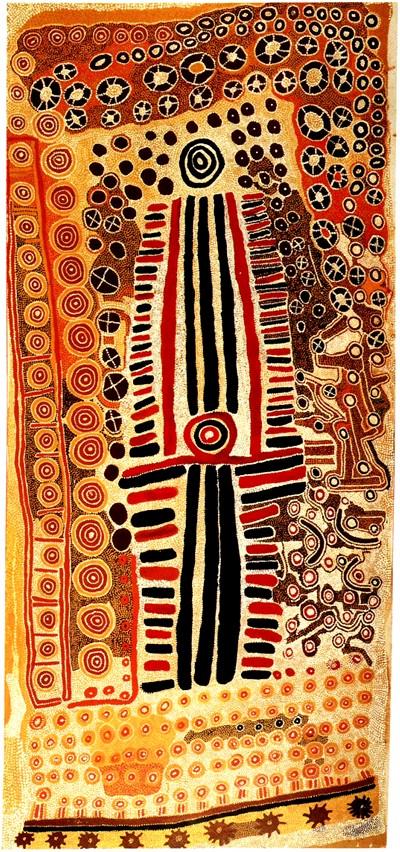

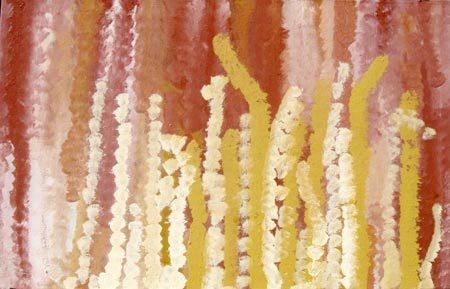

Tjala Women's Collaborative, Nganampa Ngura, 2020 (Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Award winner.

Note their utter remoteness! Nganampa Ngura means "Our Place".

Aborigines have, of course, been making “art”--that is, creating images--since ancient times, and their rock art paintings, which are still maintained and preserved, are believed to be among the oldest surviving imagery in the world. But "painting", as Westerners understand it, is, as we shall see, a very recent phenomenon.

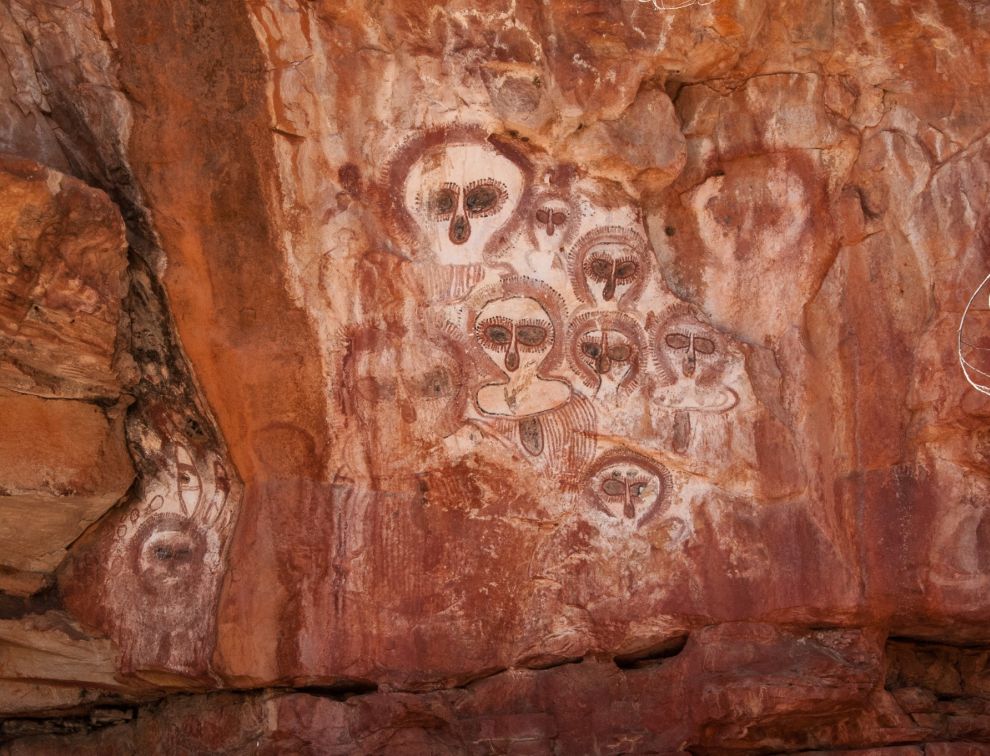

EXS: Rock art--Wandjinas,

still cared for--one of most prominent Creation

myths. Wunnumurra Gorge, Barnett River. Kimberley,

Western Australia.

Wandjina at the Sydney Olympics, 2000

From Blue Guide:

"The regional Aboriginal rock paintings centre around

Wandjina spirits. Involved in the creation myths, these

wondrous fertility guardians bring the monsoons and cyclones

to ensure regeneration of life. They are in human form with

hair that is also the area’s large, white cumulonimbus

clouds. They can cause lightning to emanate from their

feathered headdresses. The Wandjina live the dry months of

the year in their self-portrait rock paintings. During The

Wet, the local Aboriginal people preserve them by retouching

the paintings while the Wandjina themselves are away tending

to the rains."

|

|

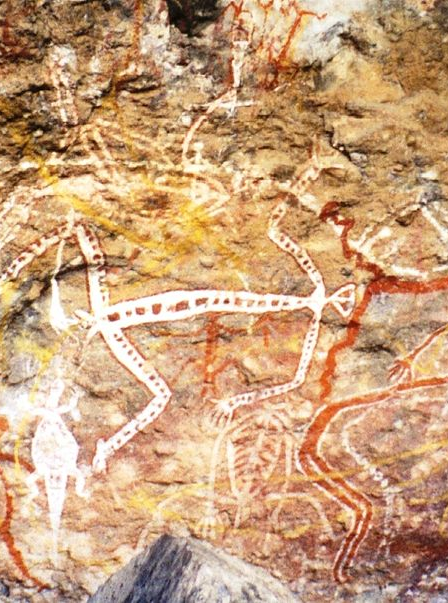

The rock art of the Kakadu region provides an interesting

insight into the process in which the convention of artistic

styles develop. Prior to the end of the last ice age, rock

art in Kakadu presented human and animal figures in animated

poses.

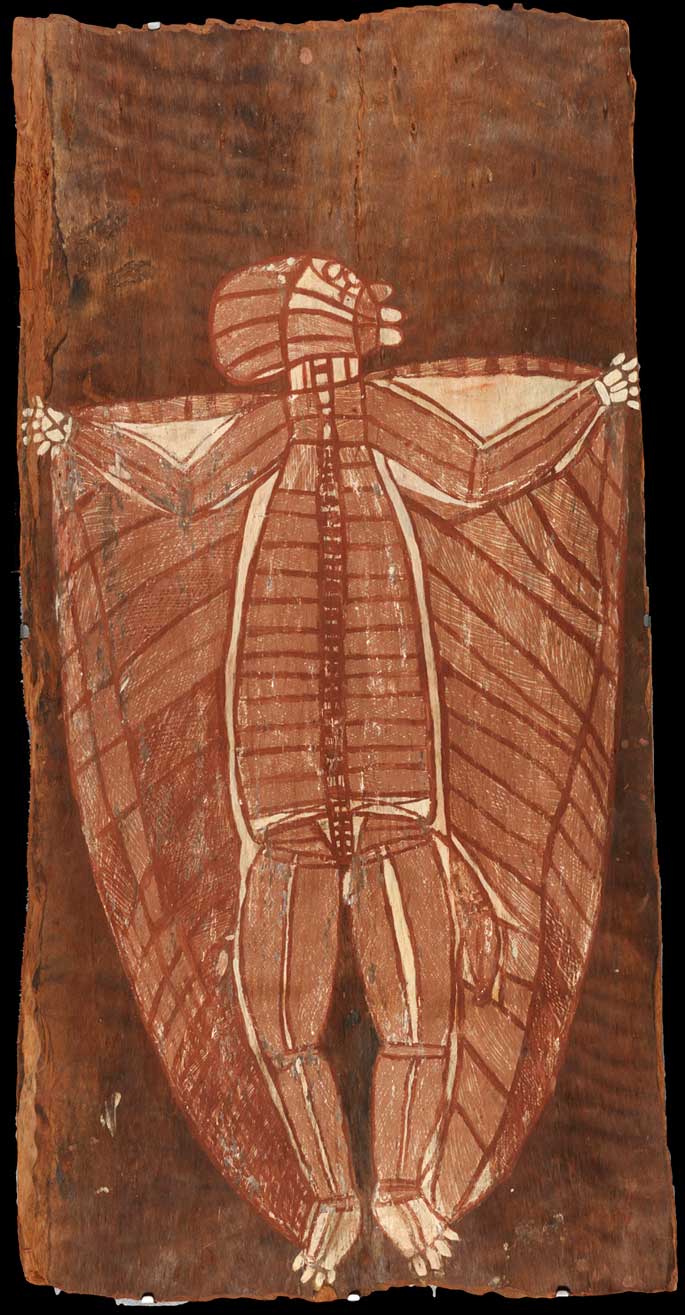

Bark paintings--used ceremonially to impart Creation

stories and initiation rites by some tribes of the

East--were found by famous explorer Baldwin Spencer in early

1900s

Bark painting collected 1912 by Spencer |

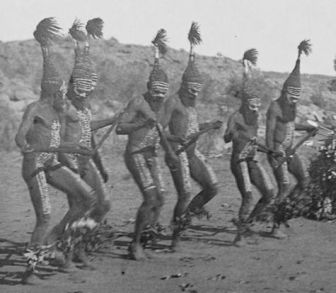

Tjitjingalla Corroboree performed in Alice Springs, 1901 |

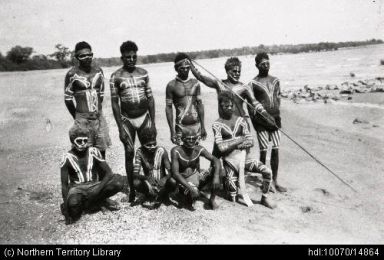

These images, and indeed almost all of Aboriginal art until very recently, were made for religious purposes--as telling parts of initiation stories--and were usually ephemeral, created in the sand or on the body as part of ceremonies

Men in initiation body paint, Cox Peninsula, 1939, photo by Bill Nicholls |

Postcard, early 20th century, showing staged Bora with sand painting, ca. 1910 |

[Bora is an initiation ceremony of the Aboriginal people of Eastern Australia, descended from groups that existed in Australia and surrounding islands before European colonisation. The word "bora" also refers to the site on which the initiation is performed. At such a site, boys, having reached puberty, achieve the status of men. The initiation ceremony differs from Aboriginal culture to culture, but often, at a physical level, involved scarification, circumcision, subincision and, in some regions, also the removal of a tooth.]

While the relative permanence of rock art makes it an

important means of dating the introduction of motifs and

styles, it was not the most frequently used medium. Painting

the bodies of celebrants in initiation and similar rites,

desert sand paintings not unlike horizontal frescos and

painted slabs of bark for the interior of dwellings were

from early days the most favoured media. Most of the motifs

found in bark and canvas paintings are secular variations on

the motifs in the consciously ephemeral body and sand

paintings.

Most important and the most cosmically ascetic aspect of Aboriginal imagery to understand: The Dreaming:

"When talking to an Aboriginal painter about a particular

work, he or she will first of all tell the visitor (as far

as the constraints of religious secrecy allow) about the

tjukurrpa (Dreaming), which is the painting’s source. He or

she will describe the specific interpretation which the

symbols assume in this story. The artist will point to the

tract of country in which the story takes place, often

naming the sites in great detail, and he will talk about the

custodianship of the area where the story is centred, naming

both specific contemporary custodians and the particular

subsection of the kin system through whom ownership is

generally passed down. For the artists, this is the

essential background information to the proper understanding

and appreciation of their work. A painting not informed by a

Dreaming (if such a thing were seriously possible) would be

nothing more than frivolous decoration; simply not art."

--Ian Green, ‘Make ’em flash, poor bugger’—-talking about

men’s paintings in Papunya in Margaret West, ed., The

Inspired Dream—Life as Art in Aboriginal Australia (1988).

Wally Caruana: “The Dreaming is a European term used by

Aborigines to describe the spiritual, natural and moral

order of the cosmos. It relates to the period from the

genesis of the universe to a time beyond living memory...The

terms do not refer to the state of dreams or unreality, but

rather to a state of reality beyond the mundane. The

Dreaming focuses on the activities and epid deeds of the

supernatural beings and creator ancestors such as the

Rainbow Serpents, the Lightning Men, the Wagilag Sisters,

...and Wandjina, who, in both human and non-human form,

travelled across the unshaped world, creating everything in

it and laying down the laws of social and religious

behavior....The Dreaming provides the ideological framework

by which human society retains a harmonious balance with the

universe--a charter and mandate that has been sanctified

over time.” (Caruana, Aboriginal Art, p. 10)

This is the framework in which we as Westerrners must consider Aboriginal art--all elements/motifs are totemic.

Aboriginal art is first and foremost representational--and, in most cases, the paintings tell a story that can have several layers of meaning.

EX: Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri, Sun, Moon and Morning Star

Tjukurrpa, 1973.

Many of its conventions are recognisable to the viewer.

Several fish of diverse species are shown caught in a large

fish trap or a kangaroo is presented in x-ray style, showing

its major organs and skeleton. With a bit of assistance the

viewer recognises the half doughnut shapes and bisected

angles in dot paintings as camp sites and emu tracks.

Beyond shared conventions, Aboriginal art in every region and in every style continues to be representational to those who understand its motifs

I want to focus on the two major styles, connected to different regions of the country:

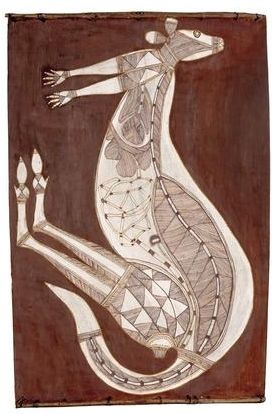

1) X-Ray style of Arnhem Land and Upper Northern Territory. In these works, the cross-hatch designs and colours represent totemic or kin groups associated with stewardship of a particular site. They can represent special relationships with the species or event depicted.

John

Mawandjul, Kandakidi, Red Kangaroo, 1997)

John

Mawandjul, Kandakidi, Red Kangaroo, 1997)

John Mawandjul, Rainbow Serpent, 1991 |

Lofty Nadjamerrek, Kolobarr, the Plains Kangaroo, 1980s. (depicting “rarrk”) |

Just as one learns representational conventions in order to interpret a painting, there are associated stories and observations learned by Aboriginal initiates. The extent of esoteric knowledge conveyed by the art, a painting for instance, depends upon the status of the observers. Still, a considerable amount of information about a painting is secular. The meaning of the cross-hatches, on the other hand, is not explained; they seem simply decorative to the uninitiated observer, while to the initiated and those skilled in looking, these signs take on additional representational and symbolic significance

Rainbow Serpent is a creation symbol story shared by

several tribes/groups, so it appears in many regions.

The serpent as a Creation Being is perhaps the oldest

continuing religious belief in the world, dating back

several thousands of years. The Rainbow Serpent features in

the Dreaming stories of many mainland Aboriginal nations and

is always associated with watercourses, such as billabongs,

rivers, creeks and lagoons. The Rainbow Serpent is the

protector of the land, its people, and the source of all

life. However, the Rainbow Serpent can also be a destructive

force if it is not properly respected. The most common

version of the Rainbow Serpent story tells that in the

Dreaming, the world was flat, bare and cold. The Rainbow

Serpent slept under the ground with all the animal tribes in

her belly waiting to be born. When it was time, she pushed

up, calling to the animals to come from their sleep. She

threw the land out, making mountains and hills and spilled

water over the land, making rivers and lakes. She made the

sun, the fire and all the colours.

Warmun community artist Rover Thomas’s magnificent

depiction of Cyclone Tracy, a black path through coloured

landscape, is easily recognised once its significance is

explained.

Rover Thomas (Joolama), Cyclone Tracy, 1991, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. |

|

Then on Christmas Eve 1974,

Cyclone Tracy destroyed Darwin. The city was regarded by

Aboriginal people of the Kimberley as the centre of

European culture and, as cyclones, rain and storms are

usually associated with ancestral Rainbow Serpents, elders

interpreted the event as the ancestors warning Aboriginal

people to reinvigorate their cultural practices. In

Thomas' painting, the black form represents the cyclone

itself gaining intensity as it heads towards Darwin. Minor

winds, some carrying red dust, are shown feeding into the

main image.

Mark

Rothko, #20, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

“White fella paint like me, but he don’t

know how to use black”

As an example of how these paintings work in terms of

conveying through repeated motifs an important story for an

Aboriginal group, I will concentrate on Wagilag Sisters

story

Basic aspects of this story, this songline:

The story goes that the two Wagilag sisters, one of whom

was pregnant, were fleeing their home and were being

followed by clansmen. On their travels they come across many

animals and plants and brought them in to life by naming

them. Eventually, the Wagilag sisters set up camp beside a

fertile waterhole at Mirarrmina. There, one of the sisters

pollutes the waterhole and the pregnant sister gives birth,

which causes Wititj the python to wake up angry and

incensed. Wititj creates a storm on emerging from the

waterhole and attempts to wash the two Wagilag sisters in to

the well with his downpour (the first monsoon). The two

Wagilag sisters dance and sing sacred songs in an attempt to

diffuse the situation and keep them safe, but when the

sisters become too exhausted to continue, the python is able

to swallow them up (including child and dog)! However, soon

after, Wititj develops stomach pains and groans skywards

above the land where he attracts the attention of other

great snakes who also rise up in to the sky. The great

snakes talk and they discover they all have different names

but they wonder why the python is ill. Realising he made a

mistake, Wititj lies about what he has just eaten but the

pain becomes so unbearable Wititj falls back to the land and

vomits up the sisters who regain their life from the

stinging bites of caterpillars. Undeterred, Wititj beats

them with clapsticks and eats them again. Later, the Wagilag

sister's clansmen, asleep in the hollow left by the python's

fall, were visited in their dreams by the sisters who

revealed to the clansmen the secrets of the songs and dances

which had been performed in an effort to stop the rainstorm.

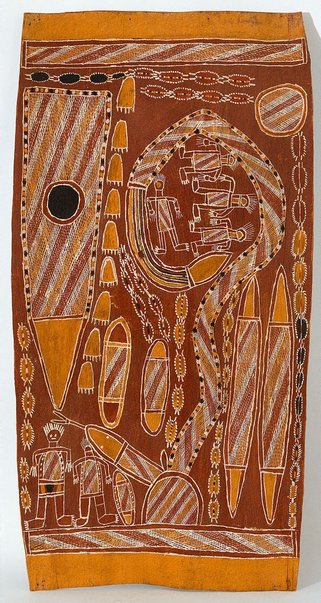

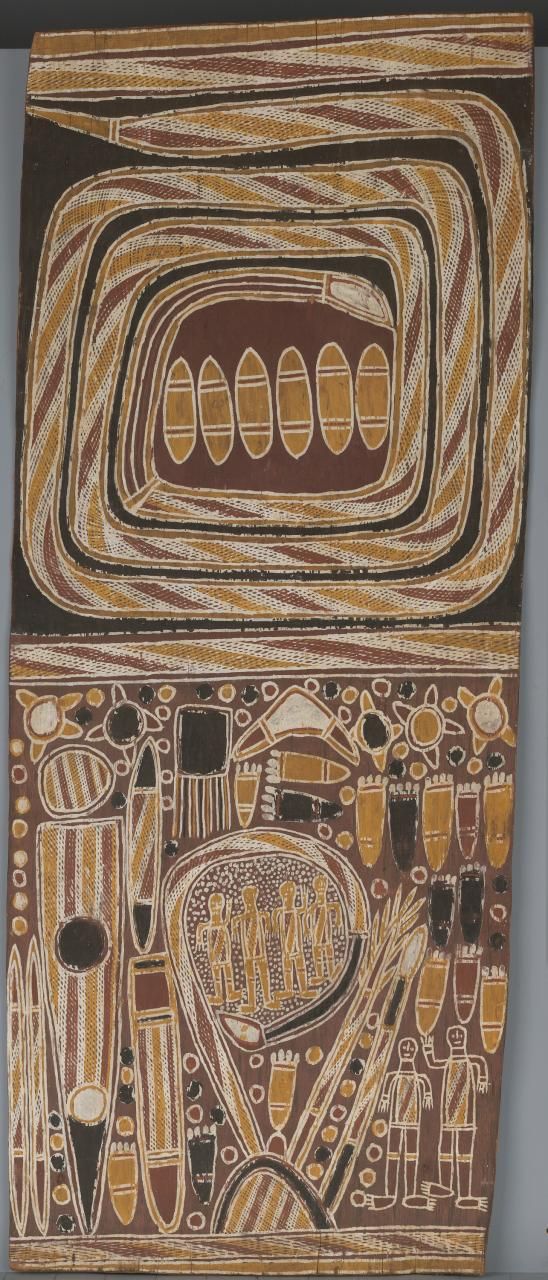

SO: as the following images indicate, this story can be

told visually in a variety of ways, in which the recurring

motifs are easily "read" by those who know the story and the

significance of its parts.

Dawidi Djulwarak, Wagilag Story, 1960. |

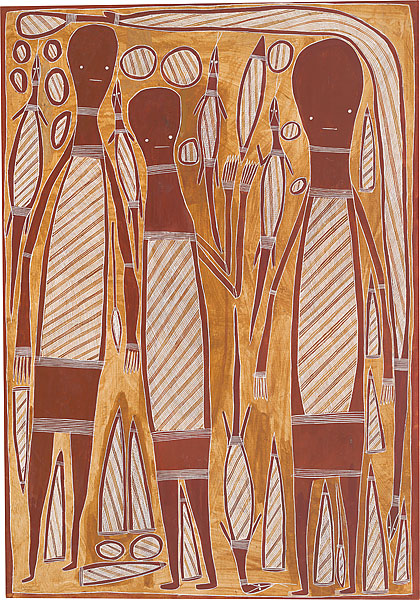

Philip Gudthaykudthay, Wagilag Sisters with child, 2007.

|

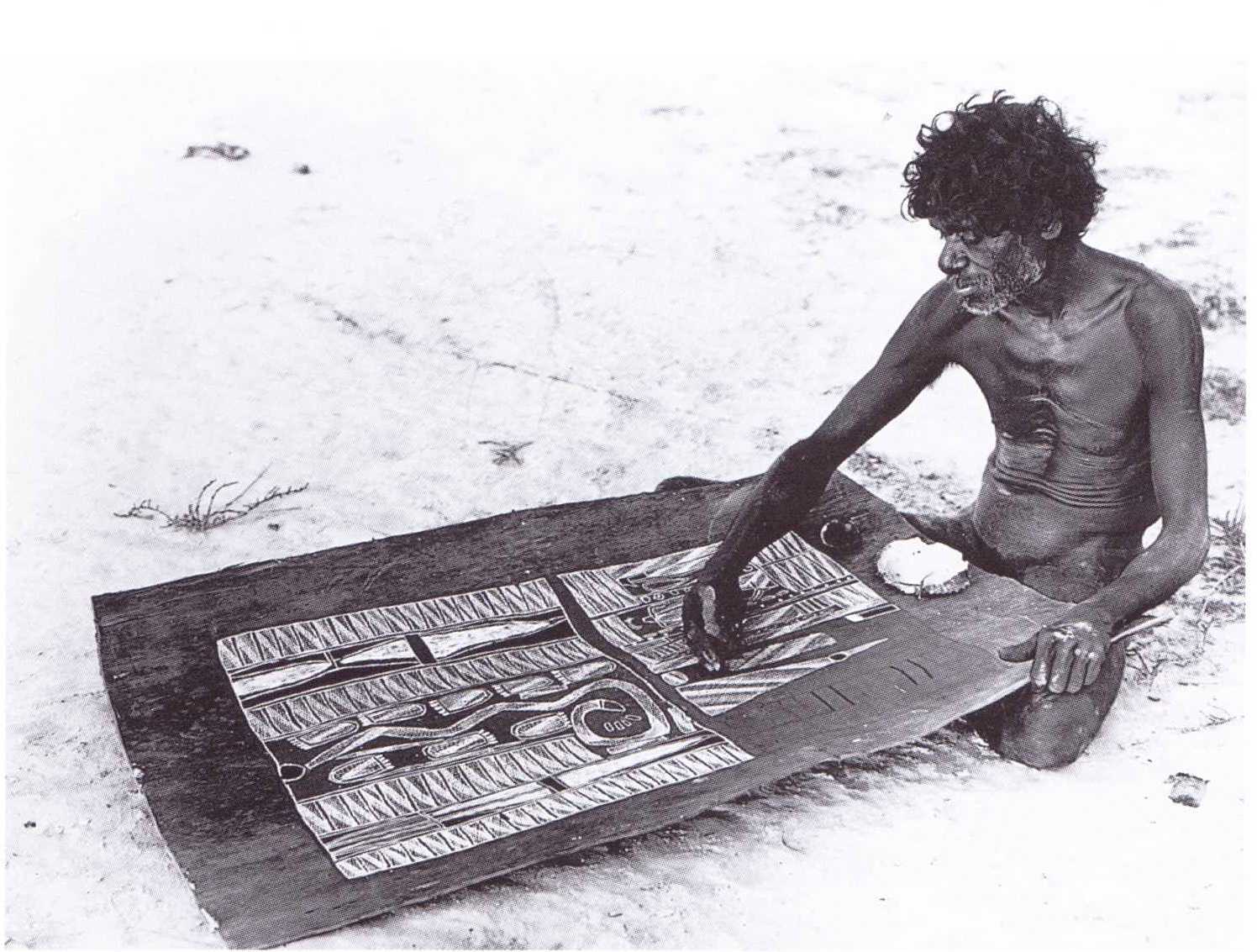

Yilkari Kitani, Wagilag Story, 1937. |

Yilkari Kitani painting this very bark 1937. |

The other great stylistic development that most of us

recognize as Aborigianl art are the so-called “dot

paintings” of the desert communities.

|

Dawidi's Wawiki |

Mick Namarari Tjapaltjar, Women's Dreaming [Women's Dreaming (No.27)] c.1973 |  John Tjakamarra, no title, c. 1973. |

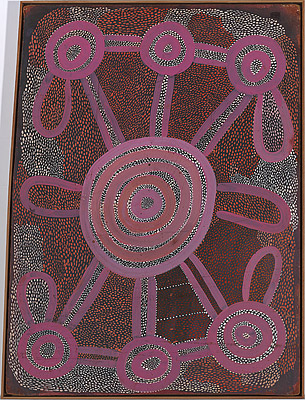

Yumari, Uta-Uta-Tjangal, 2001. |  Hogan, Kungkarangalpa, det., 2013. |

Notice the development from earlier paintings to later ones. As with the x-ray style, until quite recently, these were generally religious and ephemeral, the work being done as ground (sand) paintings, body decoration or constructions. Public awareness of the forms in the desert depended upon photographs by ethnographers, which were first taken in the early 20C, or rock art and more transportable decorations on implements seen by visitors to the region willing to brave difficult travel.

**We can trace the beginnings of this style, and of what we

call contemporary Aboriginal art, to a single moment and place:

Papunya in the early 1970s.

Of course, there had been a recognition of some Aboriginal art

from earlier times, but collected by anthropologists and

ethnographers:

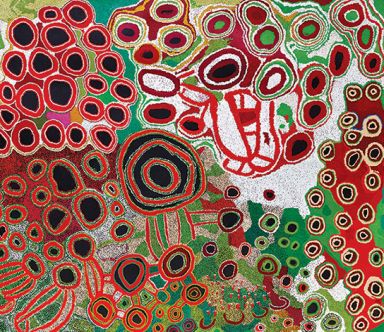

e.g. 1947 Yirkala drawings, made for the anthropologists Ronald

and Catherine Berndt on butcher paper--extraordinary example of early transmission

of Yirkala people’s storylines.

|  |

Bark painting began to be sold in the early 1960s. However, in

this case the impetus was from outstation missionaries who

attempted unsuccessfully to introduce watercolours. So, in

effect, Aboriginal art has been available to the wider public

since the 1960s. Of course, a number of anthropological and

gallery exhibits pre-date this by a century and more; German and

Swiss anthropological collections, such as the ethnographic

museum in Basel, were important archives of early Aboriginal

artefacts in Europe. The most important inaugural exhibition in

Australia was arguably the 1929 National Museum of Victoria’s

‘Primitive Art’ show, which included an anthropological display

of director Baldwin Spencer’s collection of bark paintings

acquired in 1912. But it was not until 1959 that any Australian

art gallery began to collect Aboriginal work as art rather than

as ethnographic artifacts, when the Art Gallery of New South

Wales under artist and curator Tony Tuckson began to display

works by artists from Tiwi and Arnhem Land cultures.

Tony Tuckson filming Tiwi poles, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1959. |  Tiwi poles in Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, today. |

It wasn’t until the early 1970s that what we think of as modern Aboriginal art came to the attention of the broader world and entered into the elaborately monetized matrices of the art market.

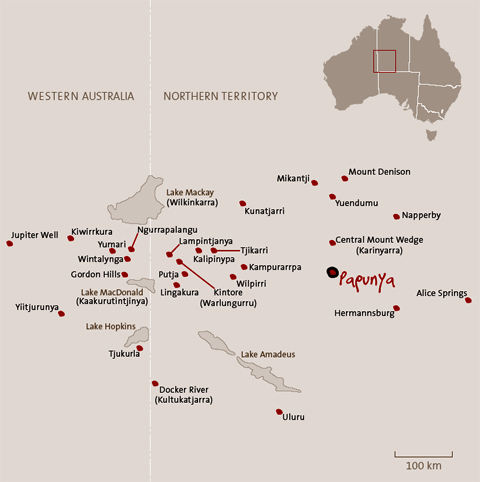

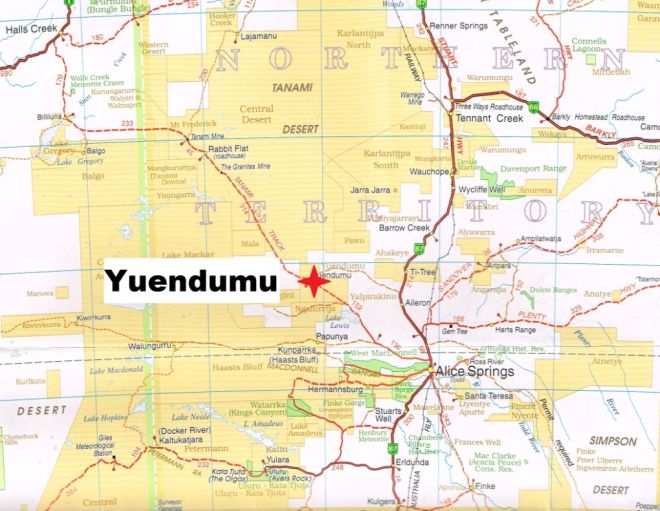

Map

of Papunya region; note Papunya, Hermannsburg, Yuendumu.

The introduction of acrylic paints to replace ground

ochres and other naturally occurring materials began in the

early 1970s at the Papunya School in central Australia. Geoffrey

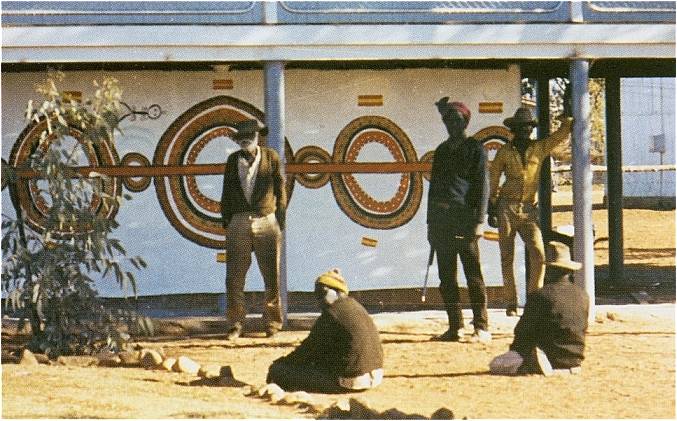

Bardon, a teacher at the school, asked senior Aboriginal men in

the community for permission and advice on the Honey Ant

Dreaming for a mural at the school.

Tribal elders and Honey Ant Mural, Papunya, NT, 1971. |  Geoffrey Bardon with Honey Ant Mural, Papunya, NT, 1972. |

Following considerable discussion about the propriety of

depicting sacred knowledge in a secular setting, Papunya elder

Old Tom Onion Tjapangati, who owned Honey Ant Dreaming, gave

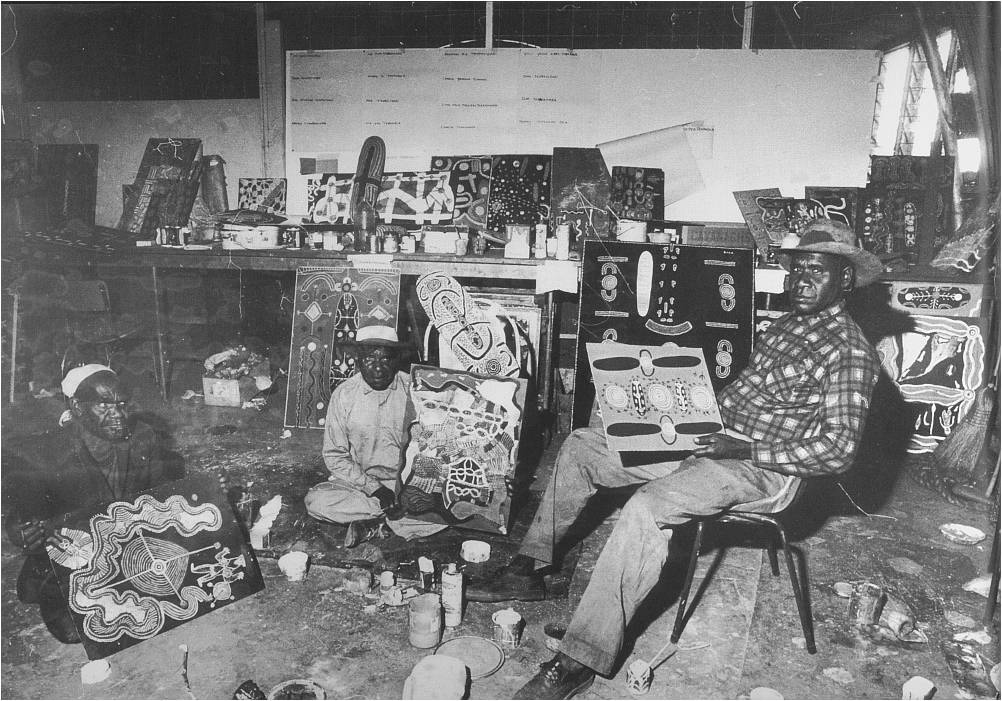

permission to a number of local men to paint the mural. At about

the same time, Bardon provided artist board and paints and with

the help of Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, one of the mural painters who

had used modern materials, the Papunya men began painting in

acrylic on board. Initially, respect for ceremonial proprieties

caused more naturalistic depictions to replace the sacred

iconography. Eventually, recognition that conventional motifs

could be described without revealing sacred secrets allowed a

return to traditional style. Art board was quickly replaced by

the more portable unstretched canvas.

Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, ater Dreaming, 1972. |  Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, Water Dreaming, 1972. |

Papunya and origin of dot paintings:

Bardon helped the Aboriginal artists transfer depictions of

their stories from desert sand to paint on canvas. They soon

realised that the sacred-secret objects they painted were being

seen not only by European, but also related Aboriginal people

which could be offended by them [5]. The artists decided to

eliminate the sacred elements and abstracted the designs into

dots [4,5] to conceal their sacred designs which they used in

ceremony.

During ceremonies Aboriginal people would clear and smooth over

the soil to then apply sacred designs which belonged to that

particular ceremony. These designs were outlined with dancing

circles and often surrounded with dots [2].

In the early years of Papunya paintings still showed clear

depictions of artefacts, sand paintings and decorated ritual

objects. But this style disappeared within a few years.

Uninitiated people never got to see these sacred designs since

the soil would be smoothed over again and painted bodies would

be washed. This was not possible with paintings. Consequently

Aboriginal artists abstracted the sacred designs to disguise the

meanings associated with them.

Some paintings are layered, and while they probably appear

meaningless to non-Aborigines, the dot paintings might reveal

much more to an Aboriginal person depending on their level of

initiation.

The first paintings to come from the Papunya Tula School of

Painters weren’t made to be sold. Papunya Tula Artists manager,

Paul Sweeney, explains that they “were produced by people who

were displaced, and living a long way from their country. The

works were visual representations of their own being. They

painted sites that they belonged to and the stories that are

associated with those sites. Essentially they were painting

their identity onto their boards, as a visual assertion of who

they were and where they were from.” [3]

A similar series of events, but with a little more awareness of

the idea of selling art to the white community, brought the art

of the Warlpiri artists of the Northern Territory to the public

arena. In this instance, Terry Davis, principal of the Yuendumu

school asked senior men to paint the doors of the community’s

school in 1983.

|  |

Sticks made by Yuendumu women, early 1980's |  |

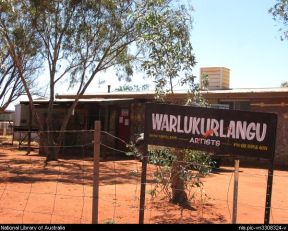

The work would be public, and would be the basis for subsequent, saleable art which would not be ephemeral but would be purchased and would permanently leave the community. That it could subsequently be sold beyond benefit to the community or the artist was not an understanding at this point. In 1985, arrangements for the secularisation of the art were made in Yuendumu through the Warlukurlangu Artists Association, one of the first Aboriginal-run organisations to benefit from commercial sales of traditional artworks.

|

|

Paddy Simms, Yuendumu, 1980s. |  Yuendumu door, Yuendumu, NT, 1983. |

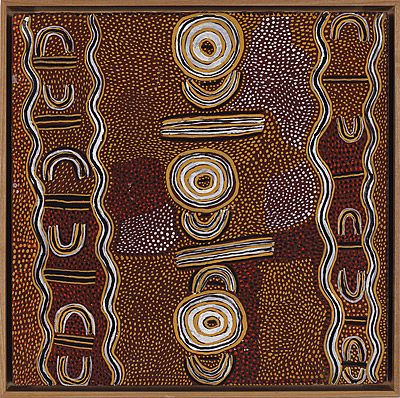

Paintings by first Yuendumu artists, Nine of the

30 Yuendumu doors, now in South Australian Museum.

Yanjilypiri Jukurrpa (Star Dreaming), 1985. Artists Paddy Jupurrurla Nelson (Warlpiri people, 1919-1999) Paddy Japaljarri Sims (Warlpiri people, 1917-2010) ,and Kwentwentjay Jungurrayi Spencer (Warlpiri people, 1919-1990). Yuendumu artists have become some of the best known artists of the movement. This painting is on the cover of Wally Caruana's book.

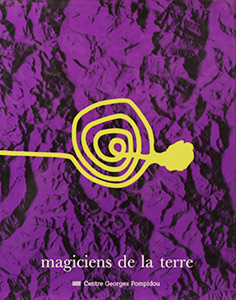

Pompidou exhibit catalog cover |  Yams in France |

One of the exhibit's rooms.

In 1989, six Yuendumu artists out of the Warlukurlangu Artists community installed a Yam Dreaming painting in the exhibition ‘Magiciens de la terre’ at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. This exhibition marked a significant point in the recognition of Aboriginal art abroad, and in a ‘high art’ context rather than as ethnographic artifact. This exhibition was a huge turning point in the recognition of all indigenous art, from Africa and the Americas as well as Australia.

For Aboriginal art, the real beginnings of the ever-vexed interactions between ancestral imagery and the voracious Western art world.

|

|

Aboriginal art on display at Sydney gallery, Danks Street,

Waterloo, NSW, 2010.--in typical art gallery context:

white walls, framed, displayed as if Abstract Expressionism

This brings us to Emily Kngwarreye, the epitome of this

interaction.

Born in 1910, Kngwarreye did not take up painting seriously

until she was nearly 80. She lived in the Anmatyerre language

group at Alhalkere in the Utopia community, about 250 km

north east of Alice Springs. Emily's initial artistic training

was as a traditional Indigenous woman, preparing and using

designs for women's ceremonies. Her training in western

techniques began, along with that of the rest of the Utopia

community, with batik. Her first batik cloth works were created

in 1980.[2] Later she moved from batik to painting on canvas:

"I did batik at first, and then after doing that I learned more

and more and then I changed over to painting for good...Then it

was canvas. I gave up on...fabric to avoid all the boiling to

get the wax out. I got a bit lazy - I gave it up because it was

too much hard work. I finally got sick of it...I didn't want to

continue with the hard work batik required - boiling the fabric

over and over, lighting fires, and using up all the soap powder,

over and over. That's why I gave up batik and changed over to

canvas - it was easier. My eyesight deteriorated as I got older,

and because of that I gave up batik on silk - it was better for

me to just paint."

Acrylic paintings were introduced to Utopia in 1988-89 by Rodney

Gooch and others of the Central Australian Aboriginal Media

Association.

Whereas the predominant Aboriginal style was based on the one

developed at the Papunya community in 1971 of many similarly

sized dots carefully lying next to each other in distinct

patterns, Kngwarreye created her own original artistic style.

This first style, in her paintings between 1989 and 1991, had

many dots, sometimes lying on top of each other, of varying

sizes and colours, as seen in Wild Potato Dreaming (1996).

Emily Kngwarreye, Earth’s Creation, 1994, Collection of Mbantua Gallery, Alice Springs, NT.

On 23 May 2007, her 1994 painting Earth's Creation was purchased by Tim Jennings of Mbantua Gallery & Cultural Museum for A$1,056,000 at a Deutscher-Menzies' Sydney auction, setting a new record an Aboriginal artwork. So the frenzy of dealers and get-rich-quick exploiters began.

With success came unwanted attention. Many other inexperienced

art dealers would go to her community to try to get a piece of

the action, Kngwarreye once describing to a friend how she had

"escaped from five or six carloads of 'wannabe' art dealers at

Utopia".

According to Sotheby's Tim Klingender, Emily was "an example of

an Aboriginal artist who was relentlessly pursued by

carpetbaggers towards the end of her career and produced a large

but inconsistent body of work."

Emily Kngwarreye , Emu Woman 1988–89

Emily Kngwarreye , Emu Woman 1988–89

The Holmes à Court Collection, Heytesbury.

Emily Kngwarreye, Emu Tracks, 1991.

Emily Kngwarreye, Emu Tracks, 1991.

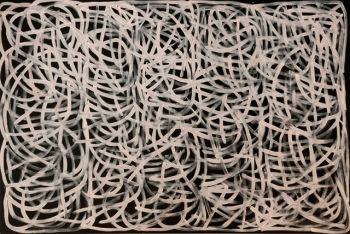

Emily Kngwarreye, Arlatyite Dreaming (Pencil Yam),

1995.

Emily Kngwarreye, Arlatyite Dreaming (Pencil Yam),

1995.

Emily Kngwarreye, Yam Dreaming, 1995.

Emily Kngwarreye, Yam Dreaming, 1995.

In 2008, a major exhibition of Emily’s work in Japan extremely

successful.

Emily exhibition, Japan, 2008. |  Margo Neale at the Japan exhibition |

About the exhibition, patron Mrs. Holms a Court's statements were described thus: “Speaking at the blockbuster opening of the Emily Kame Kngwarreye exhibition in Tokyo last night, the patron of indigenous art declared that the debate about its value was also over. 'This exhibition takes the life out of the debate about indigenous arts versus non-indigenous art,' she said. 'Kngwarreye has been anointed as not just a great indigenous artist, which she is, but a great artist full stop.' Kngwarreye was 'up there with Monet, Modigliani and all the rest', Mrs Holmes a Court added. 'Raises enormous questions of artistic appreciation: critics scorning those who apply Western aesthetic standards to her work, insulting to take works out of ethnographic context, etc.'

What do we do with the fact that we as Westerners respond to

these works aesthetically? This question still rages, as

some still reject the idea that Westerners should be allowed to

treat these images as commodified art objects, rather than as

aspects of Aboriginal communities' religious practices.

Finally, one look at one Aboriginal artist who has been trained

in Western art, of which there are now many:

Lin Onus, some of the most iconic Australian pieces today.

Lin Onus, Fruit Bats, 1991, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. |  Lin Onus, Fruit Bats, 1991, detail. |

Lin Onus, Dingoes, 1989, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

His themes are Aboriginal and political, but forms are Western--is this Aboriginal art?

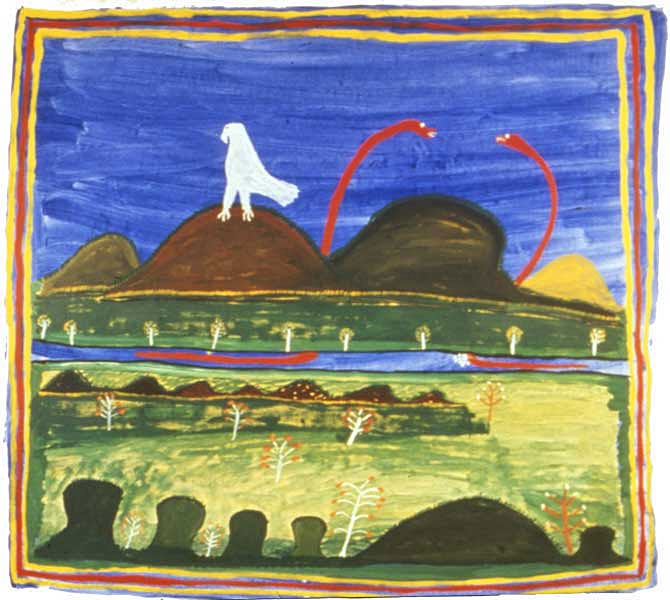

Finally, another conundrum: Ginger Riley, a tribal artist but his style is frankly folk art--is this a further development of Aboriginal style?

Ginger Riley Munduwalawala, This is my country – This is my story, 1992. |  Ginger Riley Munduwalawala Ngak Ngak in Limmen Bight Country, 1994. |

Australian

passport with Uta-Uta Tjangal’s Yumari design.

Australian

passport with Uta-Uta Tjangal’s Yumari design.

Finally, I will end with Harold Thomas, designer of the Aboriginal flag, which now flies everywhere in Australia.

Aboriginal

Flag

Aboriginal

Flag

Harold Thomas, creator of the Aboriginal flag.

Harold Joseph Thomas (born c 1947) is an Indigenous Australian descended from the Luritja people of Central Australia. An artist and land rights activist, he is best know for designing and copyrighting the Australian Aboriginal Flag.

Thomas designed the flag in 1971 as a symbol of the Indigenous land rights movement. In 1995 the flag was made an official "Flag of Australia". He was later involved in a high-profile case in the Federal Court and the High Court to assert copyright over his design.